In reading about permaculture, one strange word comes up in book after book: hugelkultur. Hugel is for hill, kultur for culture, as in cultivation. In practice, a hugelkultur pile is a giant raised bed with a base of rotting wood.

In reading about permaculture, one strange word comes up in book after book: hugelkultur. Hugel is for hill, kultur for culture, as in cultivation. In practice, a hugelkultur pile is a giant raised bed with a base of rotting wood.

Having an abundance of excess wood from downed limbs and trees, and needing to build beds for our seedlings, led us to experimentation with hugelkultur.

The Hulgelkultur Concept

Hulgelkultur is a prominent feature of many permaculture gardens. Hulgelkultur piles:

- expand growing capacity in a small space,

- encourage microclimates,

- allow for easier harvesting,

- retain water while allowing drainage, and

- build nutrients over time.

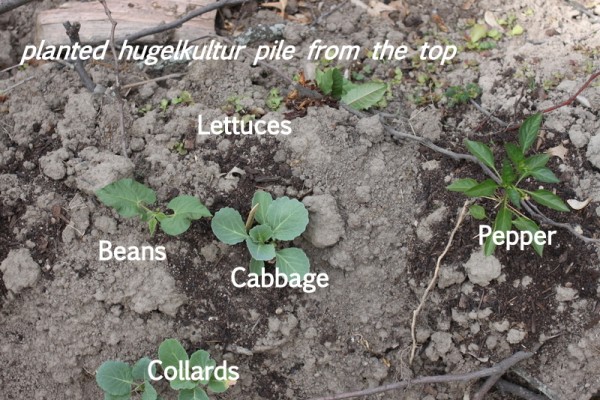

The surface area on a mini-hill, as hugelkultur piles become, allow for the greater planting area. Growers traditionally plant nutrient-needing plants like tomatoes, strawberries, peppers, etc. on the top of the pile. Heat-loving greens, like collards, line the south side where sun will be heavier, and shade-tolerant plants like lettuces go on the north side.

Building Hugelkultur Piles

The first hulgelkultur bed I built with the help of my friend Elizabeth in late winter. We took logs from a catalpa tree with very soft wood to make the base. Next we layered in smaller branches and stomped on the top to get the branches to compact. Over the next few weeks, I shoveled wood chips in the holes left behind and placed pieces of sod, upside down, over the branches to begin building soil.

The grass began growing through the sod, so I had to go back and shake out the soil piece by piece. This was tedious, but I couldn't have grasses stealing nutrients from the edibles I intended to plant. I added some soil and compost from Price Farms and planted in early May.

Later, after clearing away wood from the honey locust tree we had cut down, a big depression was left where the trunk fell. A big depression in full sun with the grass already dead? Sounds like the beginnings of another hugelkultur!

This time I was more careful to use rotten logs and grade them finely so the pile is more compact. I layered in leaf litter instead of woodchips because that's what we had in abundance.

Tips for Building Hugelkultur

- Build in the off season to allow weather to help settle everything in. Holes may appear that need to be filled.

- Digging the bottom out a little helps the layering but building right on top of the grass layer creates a higher bed.

- Quickly-rotting soft woods will build beds faster.

- Avoid materials that can leach toxins into your garden. Don't use painted or treated woods. I couldn't find definitive evidence or experience with this, but unless you have no other material available, I wouldn't use black walnut which releases juglone, toxic to plants like tomatoes and peppers.

- Build the base at least three feet wide and ideally four feet wide. Smaller widths will not hold much material on top and wider will not allow access to the middle where plants can best grow.

Our Experiments

Our second hulgelkultur is oriented opposite of the first which creates drastic differences in sunlight exposure. Both piles have tomatoes, peppers, and beans growing in them along with other plants. They piles are easy to tend, being several feet off the ground. I'm not worried about flooding in the hugelkultur piles whereas I am worried about flooding elsewhere in our low yard.

Time will tell how these hugelkultur compare to each other and to the rest of the garden made of lasagna-type beds. I predict they will be less productive in this first year as relatively fresh wood decomposes and pulls some nitrogen out of the soil. In the long term, however, I think our 'stick mound things', as guests sometimes refer to them, may become the most productive areas of our garden.